Throne, Altar, Liberty

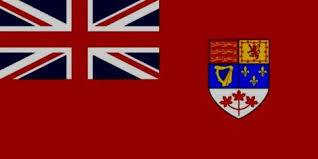

The Canadian Red Ensign

Friday, May 12, 2023

Free Unrestricted Speech is the Servant of Truth

Pelagius was a Celtic monk who lived in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. Although he was born somewhere in the British Isles, he lived most of his life in Rome until the city was sacked by the Visigoths. Following the Fall of Rome he fled to Carthage and spent the remainder of his life in the region of North Africa and Palestine. This was hardly a quiet retirement for it was in this period that the preaching of his disciple Caelestius brought him increasingly under the scrutiny of St. Augustine of Hippo and St. Jerome and led to his teachings being condemned by multiple regional synods, his excommunication by Innocent I of Rome in 417 AD, and finally, the following year which was the year of his death, the most sweeping condemnation of his teachings as heresy at the Council of Carthage, the rulings of which would later be ratified by the third Ecumenical Council at Ephesus in 431 AD making the condemnation of Pelagius and Pelagianism the verdict of the whole Church in the days before her ancient fellowship was broken.

What did Pelagius teach that was so vehemently rejected by the early, undivided, Church?

Pelagianism was the idea that after the Fall man retained the ability to please God and attain salvation through his own efforts and by his own choices unassisted by the Grace of God. Expressed as a negation of Christian truth it was a denial of Original Sin and of the absolute necessity of God’s Grace.

Over a millennium later the Protestant Reformers, strongly influenced by the teachings of St. Augustine, would read their own conflict with the Patriarch of Rome through the lens of the earlier Pelagian controversy although the Pelagian controversy had to do with the absolute necessity of God’s Grace whereas the controversy in the Reformation had to do with the sufficiency of God’s Grace. This led to further distortions of historical understanding of the earlier controversy so that in certain theological circles, particularly those who identify so strongly as Calvinists that in their hierarchy of doctrine they place the canons of the Synod of Dort in the top tier, make those matters on which all the Reformers agreed – the supreme authority of Scripture and the sufficiency of the freely given Grace of God in Christ for salvation – secondary, and assign the truths of the ancient Creeds to a tertiary position, any positive statements concerning Free Will are looked upon as either Pelagian or a step down the slippery slope to Pelagianism.

Free Will, however, is not some aberration invented by Pelagius, but a truth held by all the ancient orthodox Churches alongside Original Sin. Neither is confessed in the Creed, because neither is Creed appropriate, but both are part of the body of the supplementary truths that help us to understand Gospel truth, the truth confessed in the Creed. Free Will and Original Sin are complementary truths. Apart from Free Will, the only explanation for Adam’s having committed the sin that brought sin and death upon his descendants, is some version of supralapsarianism, the repugnant and blasphemous hyper-Calvinist doctrine of Theodore Beza that teaches that God decreed the Fall of Man to occur in order that He might have grounds to punish people He had already decided to damn.

Why did God give man Free Will if He knew man would abuse it and fall into sin?

If God had not given man Free Will, man would not be a moral creature made in God’s own image, but would rather be like a rock or a tree. Man without Free Will would have the same capacity for Good that a rock and a tree have. Rocks and trees perform their Good – the reason for which they exist – not because they choose to do so, but because they have no choice. This is a lower order of Good than the Good which moral beings do because they choose to do it. God created man as a higher being with a higher order of Good and so He gave man Free Will because man could not fulfil this higher Good without Free Will. Without the possibility of sin, there was no possibility of man fulfilling the Good for which he was created.

Original Sin impaired man’s Free Will and in doing so placed a major roadblock in the way of man’s fulfilment of the Good for which he was created. When Adam sinned he bound himself and all his posterity in slavery to sin. The ancient sages, such as Plato, urged man to employ his will in subjecting his passions to the rule of his reason or intellect. They understood that the worst slavery a man could endure is not that which is imposed from the outside by laws, customs, or traditions but that which is imposed from the inside when a man is ruled by his passions. This is the closest than man could come to understanding his plight without special revelation. When Western man in the post-World War II era turned his back on Christian truth he abandoned even this insight and began embracing the idea taught by Sigmund Freud et al. that liberating the passions rather than ruling them was the path to human happiness. Although the evidence of experience has long since demonstrated this to be folly Western man continues down this path to misery. The salvation that God has given to man in Jesus Christ frees us from this bondage to the sin principle, which rules us through what Plato called our passions and St. Paul called our flesh. This is why the work of Jesus Christ accomplishing our salvation is spoken of as redemption, the act of purchasing a slave’s freedom from bondage.

God created man in a state of Innocence which is an immature form of Goodness. Man in his Innocence possessed Free Will and was sinless but lacked knowledge and maturity. He was not intended to remain in this state but to grow into Perfection, Goodness in its mature form. The Fall into Original Sin interrupted the process of maturation and would have been ultimately fatal to it were it not for the Grace of God and the salvation given to man in Jesus Christ, our Redeemer, which Grace of salvation frees us from the bondage to sin into which we fell that we might finally grow in Christ into Perfection, the maturity of freedom with knowledge, in which we voluntarily choose the Good. If we could somehow remove man’s ability to choose evil this would in no way assist man in his journey, by God’s Grace, to Perfection. This is the Christian truth illustrated by Anthony Burgess in his novel A Clockwork Orange (1962) The experimental technique to which the narrator submitted in order to obtain a reduced sentence, succeeded in removing his ability to commit violent crime, but failed to turn him into a good person. In the novel, Alex does eventually become a better person but not as a result of the Ludovico Technique. (1)

I recently remarked that the orthodox arguments for the necessity of Free Will for man to choose the Good can also be applied to Truth to make a more compelling case for free speech than the one rooted in classical liberalism that is usually so employed. I wish to expand upon that idea here. Think again of Burgess’s novel. The Ludovico Technique rendered Alex incapable of committing violent crime – or even of acting in legitimate self defence – by causing him to experience nauseating sickness and pain at even the thought of doing the things that had landed him in prison, but it did not change his inner nature, it merely prevented him from acting on it. Now imagine a story in which a similar form of extreme aversion therapy to the Ludovico Technique is developed, not for a violent, rapist, thug but for a compulsive liar, (2) which similarly prevents him from speaking what he knows not to be true. This would not remove his internal compulsion to lie and make him naturally truthful, it would merely prevent him from acting on the compulsion.

If it is important, both to us as individuals and to the larger society to which we belong, that we develop good character by cultivating good habits, then it is important that we cultivate the habit of speaking the Truth to the best of our understanding. By adapting the lesson of Burgess’ novel as we did in the last paragraph, we saw that artificially removing the ability to do other than speak what we understand to be the Truth is not the way to achieve the cultivation of this habit. In the actual contemporary society in which we live, we are increasingly having to contend with constraints on our freedom of speech, not through experimental aversion therapy, but through laws and regulations telling us what we can and cannot say.

These come in two forms. The first and most basic are rules prohibiting speech – “you can’t say that”. The second are rules compelling speech – “you have to say this”. This distinction has in recent years been emphasized by Dr. Jordan Peterson after he ran afoul of a particularly egregious but sadly now almost ubiquitous example of compelled speech – the requirement to use a person’s expressed preference in pronouns rather those that align with the person’s biological sex. Here, the speech that is compelled is speech that falls far short of Truth. Indeed, the people who want this sort of compelled speech are generally the same people who speak of Truth with possessive pronouns as if each of us had his own Truth which is different from the Truth of others.

The rules that prohibit certain types of speech are no more respectful towards Truth. Here in the Dominion of Canada, the rules of this type that have plagued us the most in my lifetime are speech prohibitions enacted in the name of fighting “hate”. The very first in a long list of sins against Truth committed by those seeking to eradicate “hate speech” is their categorizing the speech they seek to outlaw as hateful. Hate refers to an intense emotional dislike that manifests itself in the desire to utterly destroy the object of hatred. This is a more appropriate description of the attitude of the people who call for, enact, and support “hate speech” laws towards their victims more than it does the attitude of said victims towards those they supposedly hate. The first calls for laws of this nature came from representatives of an ethnic group that has faced severe persecution many times throughout history and which, wishing to nip any future such persecution in the bud, asked for legislation prohibiting what they saw as the first step in the development of persecution, people depicting them very negatively in word and print. The government capitulated to this demand twice, first by adding such a prohibition to the Criminal Code, second by including a provision in the Canadian Human Rights Act that made the spread of information “likely to” expose someone to “hatred or contempt” into grounds for an anti-discrimination lawsuit. The CHRA provision was eventually removed from law by Act of Parliament but the present government is seeking to bring it back in a worse form, one that would allow for legal action to be taken against people based on the suspicion that they will say something “hateful” in the future rather than their having already said some such thing. The campaign against “hate speech” has from the very beginning resembled the actions taken against “precrime” in Philip K. Dick’s The Minority Report (1956) in that both are attempts to stop something from happening before it happens, but the new proposed legislation would take the resemblance to the nth degree. Early in the history of the enforcement of these types of laws the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the lack of a truth exception did not render the limitations they imposed on freedom of speech unconstitutional in Canada (Human Rights Commission) v. Taylor (1990). More recently this notion of truth not being a defense was reiterated by Devyn Cousineau of the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal in a discrimination case against Christian evangelist and activist Bill Whatcott. Whatcott had been charged with discrimination for distributing a flyer challenging a politician who had been born a biological male but who claims to be female. Cousineau made the statement in ruling against the relevance of evidence the defense intended to present as to the complainant’s biological maleness. Clearly, if the upholding of laws restricting freedom of speech on the grounds of “hate” require rulings to the effect that truth is no defense, then these laws are no servants of Truth.

That, as we have just seen, those seeking to restrict speech are serving something other than Truth, something they are willing to sacrifice Truth for, is a good indicator that it is free speech that is the servant of Truth. Further analysis confirms this. If speech is restricted by prohibitions – “you can’t say that” – then unless those who make the prohibitions are both incorruptible and infallible, it is likely that much that is prohibited will be Truth. If speech is compelled – “you must say this” – then again, unless those compelling us to speak are both incorruptible and infallible, it is likely that what we will be compelled to say will not be the Truth. The good habit of truth-telling, which we ought to seek to cultivate in ourselves, in which cultivation the laws and institutions of society ought to support us, is a habit of caring about the Truth, searching for the Truth, and speaking the Truth. Restrictions on speech, rather than helping us cultivate this habit, teach us to take the alternate, lazier, route of letting other people rather than the Truth determine what we must and must not say.

Even restrictions on speech aimed at preventing the spread of untruths ultimately work against the speaking of Truth. As long as there are such restrictions, especially if the penalties for breaking them are severe, there will be something other than Truth to which people will look to determine whether or not they should say something, and the result will be that less Truth will be spoken out of fear of running afoul of the restrictions.

The classic liberal case for free speech was made by utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill in his On Liberty (1856). It is the topic of his second chapter “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion” which begins by arguing that this freedom is necessary not only when governments are tyrannical and corrupt, but under the best of governments as well, even or especially, when governments have public opinion behind them. “If all mankind minus one were of one opinion”, Mill wrote “and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.” In support of the position taken in these justifiably famous words, Mill’s first argument was that mankind is better off for having all opinions, false or true, expressed, because the expression of the false, makes the true stand out the more. He wrote:

the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

In what he stated here, Mill was quite right. Unfortunately, what he meant by truth, small t, is not the same thing as Truth, big T. Mill wrote and thought within what might be called an anti-tradition that started within Western thought almost a millennium ago with nominalism and which has produced a downward spiral of decay within Western thought. Mill came at a late stage in this anti-tradition, although not so far down the spiral as to think that truth is entirely subjective and different for each person as so many do today. It had been set in that direction, however, by nominalism’s rejection of universals, whether conceived of as Plato’s otherworldly Forms existing in themselves or Aristotle’s embodied Ideas existing in their corresponding particulars, except as human constructions that we impose on reality by our words so as to facilitate in the organization of our thoughts. By so departing from the foundation of the tradition of Western thought, nominalism introduced an anti-tradition that over time came more and more to resemble an embrace of Protagoras of Abdera’s maxim “man is the measure of all things”. In the wisdom of the ancient sages, Truth, like Beauty and Goodness, were the supreme universals. Philosophically, they were the Transcendentals, the properties of Being or existence. In Christian theology, they existed in God Himself not as attributes or properties, but as His fundamental nature. Human happiness, however the philosophical and theological answers to the question of how it is attained differed (the Grace of God is the theological answer), consisted in life ordered in accordance with Truth, Beauty, and Goodness. Mill’s small t truth is worlds removed from this and this weakens what is otherwise a good argument against restrictions on the free expression of thought. If truth is not Truth, an absolute ultimate value in itself which we must seek and submit to upon peril of loss of happiness, but something which may or may not be available to us because we can never be certain that that what we think is truth is actually truth, then it is a far less compelling argument for allowing all thought to be freely expressed in words that it serves truth better than restrictions would. It opens the door to the idea that there is something that might be more important to us than truth, for which truth and the freedom that serves it might be sacrificed. Indeed, Mill provided the enemies of Truth and freedom with that very something else, earlier in the first, introductory, chapter of his book in which he articulated his famous “harm principle”. He wrote:

The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.

On the surface, this seems like a principle that could do nothing but safeguard people against the abuse of government power. In our day, however, we can see how it is actually a loophole allowing the government to justify any and all abuse of power. Our government, for example, is currently using it to justify its bid to bring the flow of information entirely under its own control. The Liberal Party of Canada, which is the party currently in office, has made combatting what it calls “Online Harms” part of its official platform. The Liberals’ not-so-thinly-veiled intention is enacting this goal is to bring in sweeping internet regulation that will give them total control over what Canadians can say or write or see or hear on the internet. Neither freedom nor Truth is a high priority for the Liberals, nor have they been for a long time, if they ever were. The late Sir Peregrine Worsthorne years ago wrote that by defeating its old foes, and turning its attention to declaring war “on human, and even eventually animal, pain and suffering” and thus introducing the necessity for vast expansion of government power, liberalism “from being a doctrine designed to take government off the backs of the people” had rapidly become “a doctrine designed to put it back again”, and, he might have added, in a more burdensome manner than ever before.

Mill was right that truth is better served by allowing all thoughts to be freely expressed, even false ones. Apart from the acknowledgement of Truth as Truth, the absolute unchanging universal value, however, the argument is weak. Within the context of liberalism, it is doomed to give way to that ideology’s insatiable lust to control everyone and everything, in the insane belief that it is protecting us from ourselves, and re-making the world better than God originally made it. When we acknowledge Truth as Truth, we recognize that it is what it is and that it is unchangeable and so no lie can harm it. Lies harm us, not the Truth, by getting in our way in our pursuit of Truth, but attempts to restrict and regulate the free verbal expression of thought, even when done in the name of combatting falsehoods, do far more harm of this type than lies themselves could ever do. Just as men need free will to choose the Good, we need the freedom to speak our thoughts, right or wrong, in order to pursue and find and speak the Truth.

(1) The chapter containing this ending was omitted from the American edition of the novel and from Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film adaptation based on the American edition.

(2) The idea of preventing a liar from lying has been explored in fiction. The science fiction device of truth serum is one common way of doing this. Note that the real life interrogative drugs upon which this device is based, such as scopolamine and sodium thiopental, don’t actually compel someone to tell the truth, they just make him more likely to answer questions put to him. In Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883) the title puppet, a compulsive liar, is not prevented from lying, but prevented from getting away with it, by the device of his nose growing whenever he tells a lie. Closer is the 1997 film Liar, Liar, starring Jim Carrey as a lawyer whose son is magically granted his birthday wish that his father be unable to tell a lie for 24 hours. William Moulton Marston, the inventor of the polygraph or lie detector, under the penname of Charles Marston created the comic book superheroine Wonder Woman and gave the character a magic lasso that compelled anyone trapped in it to speak the truth. None of these stories was written with the idea of the necessity of freedom of speech for genuine truth telling in mind. — Gerry T. Neal