Throne, Altar, Liberty

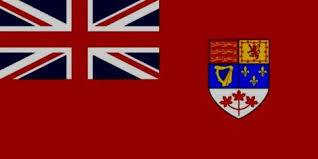

The Canadian Red Ensign

Wednesday, September 15, 2021

A Fatal Confusion

Faith, in Christian theology, is not the greatest of virtues – that is charity, or Christian love, but it is the most fundamental in the root meaning of fundamental, that is to say, foundational. Faith is the foundation upon which the other Christian theological virtues of hope and charity stand. (1) Indeed, it is the foundation upon which all other Christian experience must be built. It is the appointed means whereby we receive the grace of God and no other step towards God can be taken apart from the first step of faith. The Object of faith is the True and Living God. The content of faith can be articulated in more general or more specific terms as the context of the discussion requires. At its most specific the content of the Christian faith is the Gospel message, the Christian kerygma about God’s ultimate revelation of Himself in Jesus Christ. At its most general it is what is asserted about God in the sixth verse of the eleventh chapter of Hebrews, that “He is and that He is a rewarder of them that diligently seek Him”.

Whether articulated in its most general terms or its most specific, the faith Christianity calls for us to place in God is a confidence that presupposes His Goodness and His Omnipotence. This has led directly to a long-standing dilemma that skeptics like to pose to Christian believers. It is known as the problem of evil. It is sometimes posed as a question, at other times it is worded as a challenging assertion, but however formulated it boils down to the idea that the presence of evil in a world created by and ruled by God is inconsistent with God’s being both Good and Omnipotent. The challenge to the Christian apologist, therefore, is to answer the question of how evil can be present in a world created by and ruled by a Good and Omnipotent God. This dilemma has been raised so often that there is even a special word for theological and philosophical answers to the dilemma – theodicy.

Christian orthodoxy does have an answer to this question. The answer is a complex one, however, and we are living in an era that is impatient with complex answers. For this reason, Christian apologists now offer a simple answer to the question – free will. This is unfortunate in that this answer, while not wrong, is incomplete and requires the context of the full, complex answer, to make the most sense.

The fuller answer begins with an observation about how evil is present in the world. In this world there are things which exist in the fullest sense of the word – they exist in themselves, with essences of their own. There are also things which exist, not in themselves, but as properties or qualities of things which exist in themselves. Take redness for example. It does not exist in itself, but as a property of apples, strawberries, wagons, etc. Christian orthodoxy tells us that while evil is present in the world, it does not exist in either of these senses. It has no essence of its own. Nor does it exist as a created property of anything that does. God did not create evil, either as a thing in itself, or as a property of anything else that He created. Just as a bruise is a defect in the redness of an apple, so evil is present in the world as a defect in the goodness of moral creatures.

If that defect is there, and it is, and God did not put it there, which He did not, the only explanation of its presence that is consistent with orthodoxy is that it is there due to the free will of moral creatures. Free will, in this sense of the expression, means the ability to make moral choices. Free will is itself good, rather than evil, because without it, no creature could be a moral creature who chooses rightly. The ability to choose rightly, however, is also the ability to choose wrongly. The good end of a created world populated by creatures that are morally good required that they be created with this ability, good itself, but which carries with it the potential for evil.

One problem with the short answer is the expression “free will” itself. It must be carefully explained, as in the above theodicy, because it can be understood differently, and if it is so understood differently, this merely raises new dilemmas rather than resolving the old one. Anyone who is familiar with the history of either theology or philosophy knows that “free will” is an expression that has never been used without controversy. It should be noted, though, that many of those controversies do not directly affect what we have been discussing here. Theological debates over free will, especially those that can be traced back to the dispute between St. Augustine and Pelagius, have often been about the degree to which the Fall has impaired the freedom of human moral agency. Since this pertains to the state of things after evil entered into Creation it need not be brought into the discussion of how evil entered in the first place although it often is.

One particular dilemma that the free will theodicy raises when free will is not carefully explained is the one that appears in a common follow-up challenge that certain skeptics often pose in response. “How can we say that God gave mankind free will”, such skeptics ask us, “when He threatens to punish certain choices as sin?”

Those who pose this dilemma confuse two different kinds of freedom that pertain to our will and our choices. When we speak of the freedom of our will in a moral context we can mean one of two things. We could be speaking of our agency – that we have the power and ability when confronted with choices, to think rationally about them and make real choices that are genuinely our own, instead of pre-programmed, automatic, responses. We could also, however, be speaking of our right to choose – that when confronted with certain types of choices, we own our own decisions and upon choosing will face only whatever consequences, positive or negative, necessarily follow from our choice by nature and not punitive consequences imposed upon us by an authority that is displeased with our choice. When Christian apologists use free will in our answer to the problem of evil, it is freedom in the former sense of agency that is intended. When skeptics respond by pointing to God’s punishment of sin as being inconsistent with free will, they use freedom in the latter sense of right. While it is tempting to dismiss this as a dishonest bait-and-switch tactic, it may in many cases reflect genuine confusion with regards to these categories of freedom. I have certainly encountered many Christian apologists who in their articulation of the free will theodicy have employed language that suggests that they are as confused about the matter as these skeptics.

Christianity has never taught that God gave mankind the second kind of freedom, freedom in the sense of right, in an absolute, unlimited, manner. To say that He did would be the equivalent of saying that God abdicated His Sovereignty as Ruler over the world He created. Indeed, the orthodox answer to the problem of evil dilemma is not complete without the assertion that however much evil may be present in the world, God as the Sovereign Omnipotent Ruler of all will ultimately judge and punish it. What Christianity does teach is that God gave mankind the second kind of freedom subject only to the limits of His Own Sovereign Rule. Where God has not forbidden something as a sin – and, contrary to what is often thought, these are few in number, largely common-sensical, and simple to understand – or placed upon us a duty to do something – these are even fewer – man is free to make his own choices in the second sense, that is to say, without divinely-imposed punitive consequences.

Today, a different sort of controversy has arisen in which the arguments of one side confuse freedom as agency with freedom as right. Whereas the skeptics alluded to above point to rules God has imposed in His Sovereign Authority limiting man’s freedom as right in order to counter an argument made about man’s freedom as agency, in this new controversy man’s freedom as agency is being used to deny that government tyranny is infringing upon man’s freedom as right.

Before looking at the specifics of this, let us note where government authority fits in to the picture in Christian orthodoxy.

Human government, Christianity teaches, obtains its authority from God. This, however, is an argument for limited government, not for autocratic government that passes whatever laws it likes. If God has given the civil power a sword to punish evil, then it is authorized to wield that sword in the punishment of what God says is evil not whatever it wants to punish and is required, therefore, to respect the freedom that God has given to mankind. Where the Modern Age went wrong was in regarding the Divine Right of Kings as the opposite of constitutional, limited, government, rather than its theological basis. Modern man has substituted secular ideologies as that foundation and these, even liberalism with all of its social contracts, natural rights, and individualism, eventually degenerate into totalitarianism and tyranny.

Now let us look at the controversy of the day which has to do with forced vaccination. As this summer ends and we move into fall governments have been introducing measures aimed at coercing and compelling people who have not yet been fully vaccinated for the bat flu to get vaccinated. These measures include mandates and vaccine passports. The former are decrees that say that everyone working in a particular sector must either be fully vaccinated by a certain date or submit to frequent testing. Governments have been imposing these mandates on their own employees and in some cases on private employers and have been encouraging other private employers to impose such mandates on their own companies. Vaccine passports are certificates or smartphone codes that governments are requiring that people show to prove that they have been vaccinated to be able to travel by air or train or to gain access to restaurants, museums, movie theatres, and many other places declared by the government to be “non-essential”. These mandates and passports are a form of coercive force. Through them, the government is telling people that they must either agree to be vaccinated or be barred from full participation in society. Governments, and others who support these measures, respond to the objection that they are violating people’s right to choose whether or not some foreign substance is injected into their body by saying “it’s their choice, but there will be consequences if they choose not be vaccinated”.

The consequences referred to are not the natural consequences, whatever these may be, positive or negative, of the choice to reject a vaccine, but punitive consequences imposed by the state. Since governments are essentially holding people’s jobs, livelihoods, and most basic freedoms hostage until they agree to be vaccinated, those who maintain that this is not a violation of the freedom to accept or reject medical treatment would seem to be saying that unless the government actually removes a person’s agency, by, for example, strapping someone to a table and sticking a needle into him, it has not violated his right to choose. This obviously confuses freedom as agency with freedom as right and in a way that strips the latter of any real meaning.

What makes this even worse is that the freedom/right that is at stake in this controversy, each person’s ownership of the ultimate choice over whether or not a medical treatment or procedure is administered to his body, is not one that we have traditionally enjoyed merely by default due to the absence of law limiting it. Rather it is a right that has been positively stated and specifically acknowledged, and enshrined both in constitutional law and international agreement. If government is allowed to pretend that it has not violated this well-recognized right because its coercion has fallen short of eliminating agency altogether then is no other right or freedom the trampling over of which in pursuit of its ends it could not or would not similarly excuse. This is tyranny, plain and simple.

Whether in theology and philosophy or in politics, the distinction between the different categories of freedom that apply to the human will is an important one that should be recognized and respected. Agency should never be confused with right, or vice versa.

(1) Hope and charity, as Christian virtues, have different meanings from those of their more conventional uses. In the case of hope, the meanings are almost the exact opposite of each other. Hope, in the conventional sense, is an uncertain but desired anticipation, but in the Christian theological sense, is a confident, assured, expectation. It is in their theological senses, of course, that I mean when I say that hope and charity are built on the foundation of faith. — Gerry T. Neal