Leah Gazan’s Victim Claims Are Fraudulent: Leah Gazan Misleads Canadians on Her Family and Indian Residential Schools — Withdraw Bill C-413

·

Oct 3, 2024

Contributed by Nina Green ©2024

On 26 September 2024, NDP Member of Parliament Leah Gazan introduced a private member’s bill, Bill C-413, which would amend the Criminal Code to criminalize her fellow citizens, and subject them to two years’ imprisonment and forfeiture of property, for so- called residential school denialism.

Why is Leah Gazan trying to put her fellow Canadians in jail?

In a CTV interview on September 27, 2024 , Leah Gazan said it was personal. She was asked:

This private member’s bill is personal for you. Tell me why.

Gazan replied:

Well, you know, certainly, you know, my family has been impacted by residential school.

Is that true? Did residential schools impact Leah Gazan’s family?

The short answer is ‘No’.

Let’s look at Leah Gazan’s family tree.

On her father’s side, Leah Gazan is Jewish, Polish and Dutch. Her father, Abraham (Albert) Gazan , and his parents and sister found refuge in Canada after World War II.

There is obviously no residential school impact on her family on her father’s side.

On her mother’s side, she is of Chinese and Lakota descent. Her mother, Marjorie LeCaine , was the daughter of Adeline LeCaine and a Chinese father whose name is apparently unknown.

There is obviously no residential school impact on her family on her maternal grandfather’s side.

That leaves her maternal grandmother, Adeline LeCaine, who was the daughter of John LeCaine (1890–1964), who in turn was the son of a Lakota woman, Tasunka Nupawin (1868–1940), also known as Emma Loves War.

Was there residential school impact on Leah Gazan’s maternal grandmother Adeline’s side of the family?

Let’s see what the historical records say.

The Lakota seeks refuge in Canada

In 1877, Chief Sitting Bull and other Lakota Indians fled to Canada to seek refuge after the massacre at the Little Big Horn . Sitting Bull returned to the US in 1881 to surrender to American authorities, but 250 Lakota remained behind at Wood Mountain in Saskatchewan, among them the family of Leah Gazan’s great-great-grandmother, Emma Loves War.

In 1888, Emma Loves War had an illegitimate daughter, Alice LeCaine (1888–1976), by a white North West Mounted Police officer from Nova Scotia, William Edward Archibald LeCain (1859–1915), who in 1881 was stationed at Wood Mountain . In 1885, LeCain was involved in putting down the Riel Rebellion . He later moved to the US, where he married, worked as an interpreter, scout, teacher and writer and died in Minnesota in 1915. Although Emma’s relationship with Lecain was brief, succeeding members of her family took his surname.

After her relationship with William Edward Archibald LeCain, and the birth of her illegitimate daughter, Alice, Leah Gazan’s great-great-grandmother, Emma Loves War, had a son, Leah Gazan’s great-grandfather, John LeCaine (1890–1964). At about that time she is said to have married a Lakota husband named Okute , although there is no known record of the marriage.

Get Michelle Stirling’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

Leah Gazan’s great-grandfather, John LeCaine (1890–1964), may have been Emma’s son by her Lakota husband Okute. The problem with that assumption is that for most of his life, Leah Gazan’s great-grandfather, John LeCaine, was considered non-status and a half-breed by the Department of Indian Affairs, which suggests that although his mother, Emma Loves War, was Indian, his father was not. As Claire Thomson says on page 338 of her thesis, Digging Roots , ‘The term “half-breed” in the Lakota context was used to signify those that had white fathers’, and Thomson is uncertain as to whether Emma married Okute before or after John LeCaine’s birth in 1890 (see page 103).

At this point, residential schools enter Leah Gazan’s family history, but in unexpected ways.

Emma’s daughter Alice and son John attended the Regina Industrial School

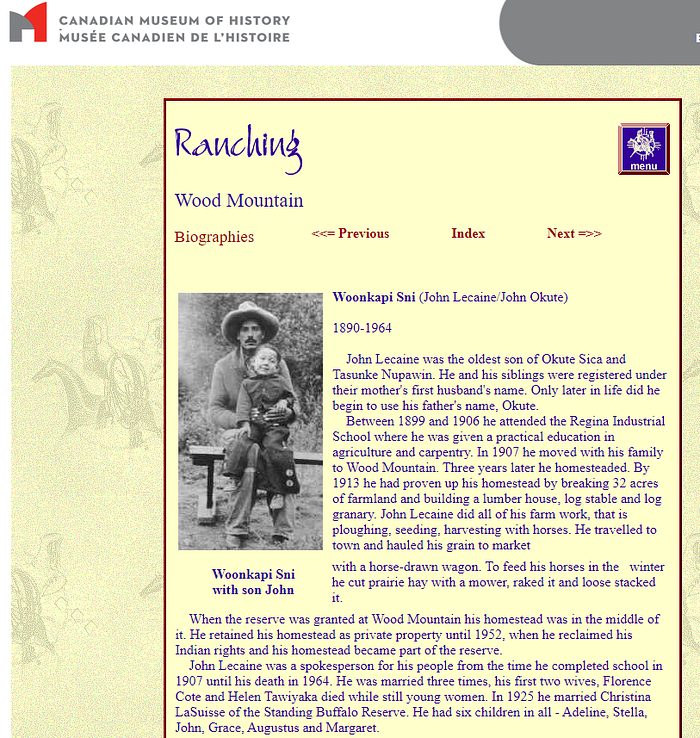

Despite being non-status, both Emma’s illegitimate daughter, Alice LeCaine (1888–1976), and Emma’s son, John LeCaine (1890–1964), were allowed to attend the Regina Industrial School. John attended for seven years, from 1899–1906 . Judging from his later accomplishments, he benefited greatly from the experience. He learned to read and write English and became a writer and historian of his people, and he learned carpentry and agricultural skills, which enabled him to file for a homestead (yes, Leah Gazan’s great-grandfather was a settler, as were other members of the LeCaine family). Alice also had a successful life, and died in the US as Alice Mahto in 1976.

John LeCaine’s children were not allowed to attend residential school

Leah Gazan’s great-grandfather, John LeCaine (1890–1964), married three times, and had several children, including his daughters Adeline (Leah Gazan’s grandmother) and Stella, who were half-sisters.

Having had a successful residential school experience himself, in 1930 Leah Gazan’s great-grandfather, John LeCaine, signed an application to have his daughter Stella enrolled in the Qu’ Appelle Indian Residential School, and the principal, Father Leonard, enrolled Stella pending approval from the Department of Indian Affairs. However, the Department took issue with John LeCaine’s application as well as with other applications from what the Department termed ‘halfbreeds’, as summarized by Claire Thomson on page 336 of her thesis:

Indian Commissioner WM Graham also wrote on this issue in 1930 and provided a different angle for deciding which children were Indian or not when responsibility for schooling was concerned: “You are aware that at one time (about 15 years ago) nearly half of the children in this school [Qu’Appelle Residential School] were halfbreeds. We succeeded in getting every one of them out, and made it a hard and fast rule that the only halfbreed children who could be admitted were those who were living on an Indian reserve as Indians.”9 Therefore, in 1930 HE King, overseer of the Wood Mountain Reserve, was asked about the children’s parents and supplied information showing that John Lecaine, Charles Lecaine, Albert Brown, and Jimmie Ogle, were “all white and Indian halfbreeds. Are all voters or at least entitled to vote” and all either lived off the reserve, in the town of Wood Mountain, or owned property in the area.10

As a result of Commissioner Graham’s letter (see RG10, 660–10, Part 1 ), John LeCaine’s daughter, Stella, was discharged from the Qu’ Appelle Indian Residential School on the ground that she was ineligible to attend since her father was a halfbreed , entitled to vote, and lived off reserve on his own homestead.

It goes without saying that since the Department did not permit John LeCaine to enroll his daughter Stella, the Department would not have allowed him to enroll his other daughter, Adeline, Leah Gazan’s grandmother, either.

We thus see that the impact of residential school attendance on Leah Gazan’s family was positive, not negative. Her great-grandfather, John LeCaine (1890–1964) attended the Regina Industrial School and acquired the skills to lead a very successful life as a homesteader, writer, and historian (see his obituary in the April 1964 issue of the Indian Record and the 20 March 1964 issue of the Regina Leader-Post ). His sister Alice also acquired the skills to lead a successful life.

On the other hand, Leah Gazan tells us that her grandmother Adeline, who was not allowed to attend residential school, did not experience the same success.

Leah Gazan makes her grandmother Adeline’s abandonment of her children a matter of public record

In the 1931 census , Leah Gazan’s grandmother, Adeline Lecaine, was listed as 14 years old, and living with her father, John LeCaine (1890–1964), on his homestead. However by 1941, Adeline’s life had gone off the rails, and she was in Moose Jaw with two illegitimate children, one of whom was Leah Gazan’s mother, Marjorie (1936–2007). Leah Gazan made her grandmother Adeline’s abandonment of her two children in a hotel room in Moose Jaw a matter of public record on September 18, 2023 when she told Parliament :

I want to share a story about my mother. My mother, Marjorie Gazan, was a street kid and a child welfare survivor who ended up in the system after my grandmother [Adeline] abandoned her and her younger brother in a hotel room in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, when she was five years old.

My grandmother [Adeline] had to leave them to earn money. There were no supports for indigenous women in the 1930s. There were no human rights. There was no one to turn to, especially for indigenous single mothers, and my grandmother was not an exception.

Since my mother was the eldest child, my grandmother left her in charge of her younger brother with specific instructions. She said, “Here is a loaf of bread, peanut butter and jam. It needs to last five days.” I remember my mother telling me how she, along with my uncle, gleefully ate the loaf of bread and ran out of their food ration in only one day. Hungry, scared and alone, my mother decided to call the Children’s Aid Society.

As mentioned earlier, Leah Gazan’s mother, Marjorie, was Adeline’s daughter by a Chinese father whose name is apparently unknown, and who took no responsibility for her upbringing. Thus, after Adeline abandoned her, Leah Gazan’s mother Marjorie was in the care of child welfare. Despite this, Marjorie made a success of her life, and eventually married Albert Gazan, who, as mentioned earlier, came to Canada with his parents as a Holocaust survivor from Holland where he had been sheltered during the war by Dutch families.

So why is Leah Gazan claiming that her family was negatively impacted by Indian residential schools to the point that she has tarred Canada with genocide , and wants to put her fellow Canadians in jail?

Why, instead of expressing gratitude to the country which gave refuge and opportunity to both sides of her family, does Leah Gazan want to criminalize her fellow citizens on the ground that residential schools harmed her family, when in fact the only person in her direct family tree who went to a residential school was her great-grandfather, John LeCaine (1890–1964), who learned skills there which enabled him to live a very fulfilling life?

Leah Gazan is the last person who should be putting forward this private member’s bill claiming that her family was harmed by Indian residential schools.

She should immediately withdraw the bill.

Nina Green

*

3