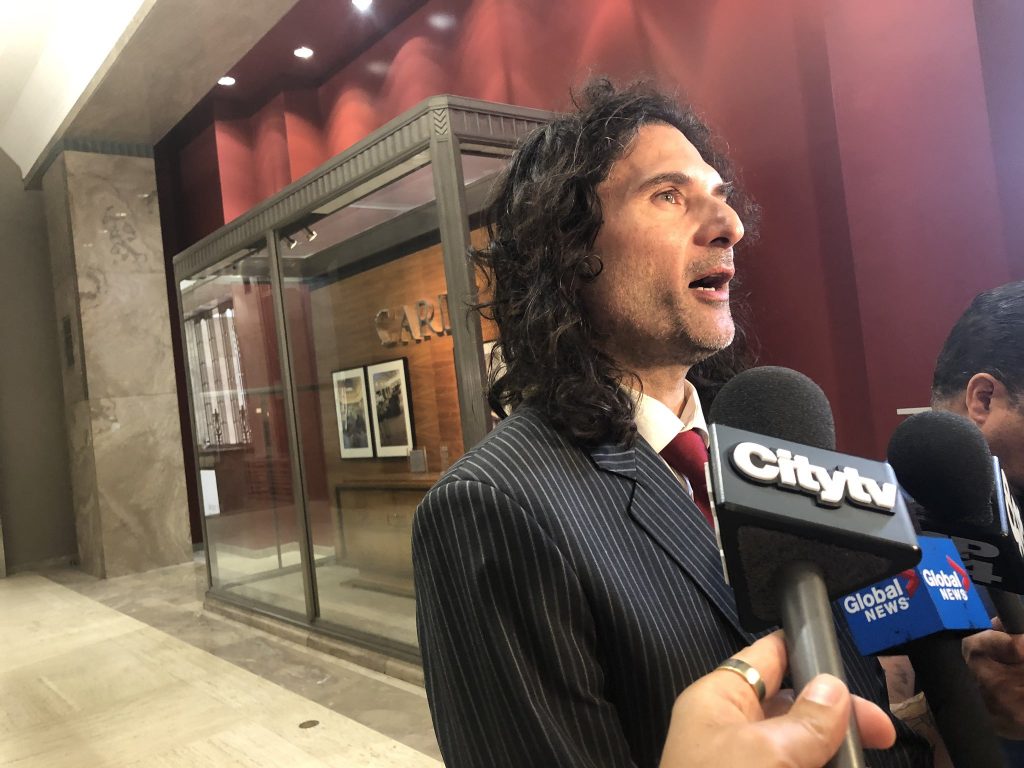

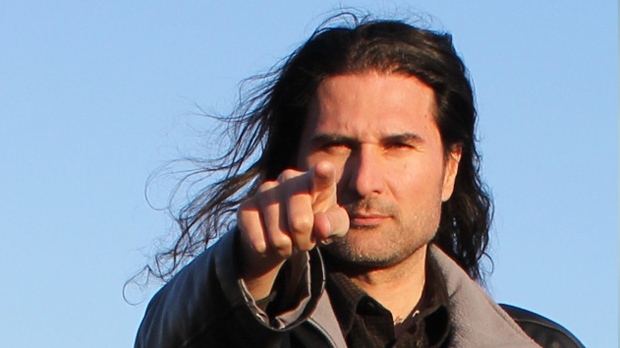

Disappointing — Political Prisoner Dr. James Sears Will Remain in Jail for Writing Politically Incorrect Satire in YOUR WARD NEWS: Court of Appeal for Ontario Won’t Grant Him Leave to Appeal

It took Motions Judge David Brown a full month to peruse Dr. James Sears’ Application for Leave to Appeal his conviction and maximum sentence of one year’s imprisonment under Canada’s notorious “hate law”, Sec. 319 of the Criminal Code for satirical writings about privileged minorities (Jews and women) in the tabloid YOUR WARD NEWS. Judge Brown in his July 16 ruling denied leave (permission) for the Court to hear Dr. Sears’ appeal.

So, a Canadian writer and newspaperman will remain in jail as a political prisoner, a non-violent prisoner of conscience in a Cultural Marxist ruled country that praises “diversity” but detests “diversity” of opinion.

Dr. Sears is being held in the South Toronto Detention Centre and is considering his legal options.

What follows is the text of Judge Brown’s ruling.

Paul Fromm

Director

Canadian Association for Free Expression

COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO

CITATION: R. v. Sears, 2021 ONCA 522

DATE: 20210716

DOCKET: M52559 & M52561

Brown J.A. (Motions Judge)

BETWEEN

Her Majesty the Queen

Responding Party

and

James Sears

Applicant

James Sears, acting in person

Ian McCuaig, assisting the applicant

Michael Bernstein, for the responding party

Heard: June 18, 2021 by video conference

ENDORSEMENT

I. OVERVIEW

[1] The applicant, James Sears, applies for leave to appeal from the order of the Summary Conviction Appeal Judge, Cavanagh J. (the “Appeal Judge”), and, if leave is granted, bail pending appeal.

[2] On January 24, 2019, the applicant and his co-accused, LeRoy (Lawrence) St. Germaine, were found guilty on two counts of willfully promoting hatred against identifiable groups – Jews and women – contrary to s. 319(2) of the Criminal Code. Neither accused testified at trial. The trial judge sentenced the applicant to a term of imprisonment of six months on each count, to be served consecutively.

[3] The convictions stemmed from statements written and published by the applicant and his co-accused in 22 issues of a newspaper called “Your Ward News” distributed in Toronto and online between January 2015 and June 2018.

[4] The applicant appealed his conviction and sentence to the Superior Court of Justice. The Appeal Judge dismissed the appeal: R. v. Sears, 2021 ONSC 4272 (“Appeal Reasons”).

[5] The applicant then applied before this court for leave to appeal his conviction and sentence pursuant to Criminal Code s. 839(1). As well, the applicant sought bail pending his appeal.

[6] The applications came before me on Monday, June 14, 2021. I advised the applicant that his application for bail pending appeal would necessarily entail a consideration of the merits of his leave to appeal application. Although I had jurisdiction to hear his application for leave to appeal[1], the practice of this court is for a panel to consider such applications in writing: Criminal Code, s. 839(1); “Practice Direction Concerning Criminal Appeals at the Court of Appeal for Ontario”, (March 1, 2017), at 7.3.6. The applicant advised that he wished to proceed before a single judge. I adjourned the hearing until Friday, June 18, 2021 to permit the applicant to file further materials.

II. GOVERNING PRINCIPLES

[7] An appeal to the Court of Appeal in summary conviction matters lies, with leave, “on any ground that involves a question of law alone”: Criminal Code, s. 839(1). The principles governing such applications for leave were summarized by this court in R. v. Lam, 2016 ONCA 850, at paras. 9 and 10, leave to appeal refused, [2017] S.C.C.A. No. 2:

Section 839(1) of the Criminal Code limits appeals to this court from decisions of summary conviction appeal courts to grounds involving questions of law alone and requires that leave to appeal be granted by this court. This second level of appeal in summary conviction proceedings is an appeal from the decision of the summary conviction appeal court, not a second appeal from the decision of the trial court. The appeal is limited to questions of law alone and does not extend to questions of fact alone or of mixed fact and law, as do appeals to the summary conviction appeal court from decisions made at trial. Second appeals in summary conviction proceedings are the exception, not the rule: R. v. R.(R), 2008 ONCA 497, 90 O.R. (3d) 641, at para. 25.

Two key variables influence the leave decision:

• The significance of the legal issue(s) raised to the general administration of criminal justice

• The merits of the proposed ground(s) of appeal.

Issues that have significance to the administration of criminal justice beyond the particular case may warrant leave to appeal, provided the grounds are at least arguable, even if not especially strong. And leave to appeal may also be granted even if the issues lack general importance, provided the merits appear very strong, especially if the conviction is serious and an applicant is facing a significant deprivation of his or her liberty: R.(R.), at para. 37.

[8] To those principles I would add two others. First, since an appeal pursuant to s. 839(1) is an appeal against the judgment of the summary conviction appeal court, not a second appeal of the trial judgment, the leave to appeal judge should determine whether the summary conviction appeal judge properly applied the principles governing appellate review of the trial decision: John Sopinka, Mark Gelowitz & W. David Rankin, Sopinka and Gelowitz on the Conduct of an Appeal, 4th ed. (Toronto: LexisNexis, 2018), at §3.119; R. v. McCammon, 2013 MBCA 68, 294 Man. R. (2d) 194, at paras. 21, 36; R. v. C.S.M., 2004 NSCA 60, 223 N.S.R. (2d) 311, at para. 26.

[9] Second, the leave to appeal test should be relaxed where the summary conviction appeal decision is, in effect, a decision of first instance, for example where the appeal court reverses a decision of the trial court by substituting an acquittal for a conviction: R. v. O’Meara, 2012 ONCA 420, 292 O.A.C. 358, at para. 25. That a new issue arose for the first time on the summary conviction appeal is an important contextual factor within which to address the R. v. R.R., 2008 ONCA 497, 90 O.R. (3d) 641, test: R. v. MacKay, 2012 ONCA 671, 112 O.R. (3d) 561, at paras. 21-22.

III. THE APPLICANT’S GROUNDS OF APPEAL

[10] The applicant acts in person. As a former medical doctor, the applicant is very articulate. However, his written materials at times lack focus or sufficient legal particularity.

[11] The applicant’s Notice of Appeal identifies six grounds of appeal, which really amount to five as the fourth and sixth grounds essentially relate to the same sentencing issue concerning the imposition of consecutive sentences. The applicant’s Notice of Application for Release Pending Appeal and Leave to Appeal repeats three of the grounds contained in the Notice of Appeal.

[12] At the hearing on June 14, the applicant was assisted by Mr. Ian McCuaig, who was counsel at trial and on appeal for the applicant’s co-accused. In response to my inquiry for a more focused statement of the questions of law alone on which the applicant seeks leave, Mr. McCuaig sent the court an email identifying three issues that the applicant considers his strongest grounds of appeal. They are:

i. A new issue arising from the conduct of the summary conviction appeal: specifically, that the mode of hearing for the appeal was changed from in-person to Zoom videoconference over the applicant’s objections, resulting in an unfair process for the appeal hearing;

ii. The Appeal Judge erred in treating the direct evidence of the actus reus – the 22 editions of Your Ward News – as direct evidence for proving the mens rea of the offences. In the applicant’s view, the newspapers were only circumstantial evidence of mens rea and the trial judge did not satisfy the requirements of R. v. Villaroman, 2016 SCC 33, [2016] 1 S.C.R. 1000, when he inferred the applicant’s intent from the contents of the newspapers he edited and wrote; and

iii. The Appeal Judge failed to address the applicant’s sentence ground of appeal that Criminal Code s. 718.2(a)(i) – treating evidence that the offence was motivated by hatred based on race or sex as an aggravating factor – did not apply to offences under s. 319(2).

[13] On these applications, I will examine those three grounds of appeal, as well as whether the Appeal Judge erred by letting the applicant’s consecutive sentences stand. Although the applicant raised a number of other complaints with the trial decision during oral argument, these four grounds of appeal were the only ones advanced with particularity in the Notice of Appeal and Notice of Application for Release Pending Appeal and Leave to Appeal.

IV. FIRST GROUND: HEARING THE SUMMARY CONVICTION APPEAL BY VIDEOCONFERENCE

The events

[14] The appeal hearing was scheduled to be heard in mid-October 2020. One issue on the appeal concerned the applicant’s allegation of ineffective assistance by trial counsel; the trial judge had dismissed an application for a mistrial by reason of ineffective assistance. Cross-examination on the affidavits relating to that issue would take place at the appeal hearing. The applicant anticipated that the hearing would be in-person as that was the default mode of hearing for self-represented persons at that point of time in the Toronto Region.

[15] A case management conference was held before Akhtar J. on October 9, 2020, who advised that because of increasing COVID-19 infection rates in Toronto the appeal would be heard by Zoom videoconference. The applicant objected, arguing that he was entitled “to see the eyes of the person that is judging me.” A discussion ensued about whether the applicant had to comply with the general rule to wear a mask when entering the courthouse and the ability of supporters of the applicant to watch the appeal. At the end of the discussion Akhtar J. ruled:

[L]isten, I apologize for the miscommunication. There’s clearly been miscommunication [indiscernible] with the court what, what happened. The means of infection is a game changer. They are surging. But I understand that there’d be over a hundred people, potentially, coming into the court and they would not be allowed in the courtroom. And who knows what they’re going to be doing, whether they’re going to be wearing masks or not, I don’t know. Mr. Sears says he won’t wear a mask because he’s exempt. He won’t be allowed into the courthouse, I can assure you of that, because that’s the rule. Mr. Sears, I’ve done my best to accommodate you, and you know that, in every single day here, to try and get this on, on the rails and keep it on the rails. But, you have no entitlement to an in-person hearing. You don’t decide the procedure here. The court does. And based on all the circumstances I’ve heard, including the fact that, as I say, there’s going to be a large crowd coming, there’s going – you’re not going to be wearing a mask, and the fact that these figures today on the COVID I’m hearing, they are going to the Zooms and it is to be a Zoom hearing, and it will be a Zoom hearing.

[16] A Zoom hearing of the appeal commenced before the Appeal Judge on October 13, 2020. The applicant again raised his objection to the appeal proceeding by way of Zoom. He also submitted, by way of a “key takeaway”, that he required additional time to prepare properly for a Zoom hearing: he had planned to use large display boards at the in-person hearing but now would have to prepare a PowerPoint slide presentation. The Appeal Judge granted the applicant’s request for a short adjournment until November 10, 2020.

[17] On November 5, a few days before the scheduled start of the hearing, the Appeal Judge heard a motion by the applicant to adjourn the appeal until it could be conducted in-person. The applicant argued that the order to proceed by Zoom conflicted with information on the court’s website stating that self-represented persons must appear in person and violated his rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

[18] The Appeal Judge dismissed the motion, ruling in part:

This was raised again before me on October 13, 2020 when the applicant appeared by audio conference only, and I granted the requested adjournment on that occasion on the basis that it would not be fair for Mr. Sears to participate in the appeal by audio conference only. And at that time Mr. Sears agreed to secure an Internet link in order to proceed by Zoom, and new dates were scheduled.

Section 715.23 of the Criminal Code provides that the court may order an accused to appear by audio conference or video conference if the court is of the opinion that it would be appropriate, having regard to all the circumstances including the five specified circumstances set out in section 715.23.

In this case the order of Justice Akhtar as the case management judge is an interlocutory order and I lack jurisdiction to hear an appeal from that order.

…

And so in my view the order of Justice Akhtar order is – [indiscernible] the order as stands and I am not allowed to interfere with it on this application. If it turns out that there was a problem with a reasonable apprehension of bias, as Mr. Sears suggests, or any other issue with respect to that interlocutory order, that is properly a matter to be addressed through appeal proceedings, if the summary conviction appeal is dismissed.

[19] Although the applicant informed the Appeal Judge that he might not appear on the first two days of the appeal hearing when the evidence on the ineffective assistance of counsel issue was scheduled, in fact he participated throughout the Zoom appeal hearing.

Positions of the parties

[20] In his Notice of Application for Release Pending Appeal and Leave to Appeal and his Notice of Appeal, the applicant states that the decision of Akhtar J. to change the mode of hearing without notice was procedurally unfair because it contravened “the stated policy of the Court that self-represented appeals would be heard in person.” The decision prejudiced the applicant “as the appeal included cross examination as part of an ineffective assistance claim, the appeal record was voluminous and the number of issues argued was significant.”

[21] The applicant submits that Akhtar J. lost jurisdiction by overruling the “stated policy of the Court”, which was the September 28, 2020 iteration of the Superior Court of Justice, Toronto Region, “Notice to Profession: Toronto Expansion Protocol for Court Hearings During COVID-19 Pandemic.” Section A.4 dealt with “matters that will continue to be heard remotely.” Subsection (viii) concerned Summary Conviction Appeals. In the section dealing with hearings, para. 4 stated:

All out of custody appellants required to attend the hearings in person are no longer required to do so, unless self-represented. Hearings for self-represented appellants/applicants shall be conducted in person, unless in custody, in which case they will be conducted remotely.

[22] In his Enhanced Book of Authorities and Unfiltered Oral Argument Notes for Summary Conviction Appeal (“Unfiltered Argument”), which the applicant filed at the appeal hearing and on these applications, he describes his objection to a Zoom appeal hearing in the following terms:

I am being denied my constitutional right to an in-person hearing, and instead, under threat of imprisonment, I have been ordered to stare into a video screen at a cluster of pixels being transmitted from the Ministry of Truth. I am told that the image formed on the screen represents the Arbitrator of Truth who I must refer to as “His Honour” and who may be a real human or an A.I. virtual image.

…

And the reason I am forbidden to meet my arbitrator in person is that the Ministry of Truth is an arm of a fascist government which conveniently claims that an invisible virus could strike dead the Ministry of Truth’s aged prosecutor. And my suggestion that he alone appear by ZOOM is rejected without a reason.

[23] The Crown submits that this ground of appeal does not involve a question of law alone. Sections 683(2.1) and 822(1) of the Criminal Code provide a summary conviction appeal judge with the statutory power to order an appeal hearing to proceed by videoconference. Akhtar J.’s exercise of that statutory power does not give rise to a question of law alone. In any event, the applicant’s particular complaints about the mode of hearing do not have significance to the administration of justice beyond the four corners of the case.

Analysis

[24] I do not understand the applicant to be taking the position that Akhtar J. lacked the power to direct a videoconference appeal hearing. That is understandable given that s. 683(2.1) of the Criminal Code, which applies to summary conviction appeals by reason of s. 822(1), states: “In proceedings under this section, the court of appeal may order that a party appear by audioconference or videoconference, if the technological means is satisfactory to the court.”[2]

[25] Instead, I understand the applicant to be arguing that Akhtar J. improperly exercised his power to order a videoconference hearing because the Notice to Profession then in force contemplated in-person hearings for summary conviction appeals where the appellant was self-represented.

[26] I am not persuaded that a challenge to a procedural decision made within the jurisdiction of a summary conviction appeal judge raises “a question of law alone” within the meaning of s. 839(1) of the Criminal Code: R. v. Bresnark, 2013 ONCA 110, at para. 7.

[27] Even if the ruling could be characterized as a breach of procedural fairness giving rise to a question of law alone, the merits of this ground are very weak for two reasons. First, as disclosed in his reasons, Akhtar J. exercised his discretion to direct a Zoom hearing at a time of increasing public health concerns with the start of the COVID-19 “second wave” in Ontario, which resulted in the cancellation of most in-person attendances. Second, the prejudice the applicant sought to avoid – namely, impediments to adducing viva voce evidence and cross-examining on the issue of ineffective assistance of counsel – evidently did not materialize for he has not sought leave to appeal the Appeal Judge’s dismissal of his ineffective assistance of counsel claim.

[28] Nor does this ground of appeal involve a matter of significance to the general administration of criminal justice: it concerns the exercise of judicial discretion on a specific set of facts at a point of time when there were unique public health concerns.

[29] Accordingly, treating this ground of appeal as a new issue arising from the appeal hearing, I do not see it satisfying even a relaxed application of the R.R. principles regarding s. 839(1) leaves to appeal.

V. SECOND GROUND: CHALLENGING THE FINDINGS ON THE ELEMENTS OF THE OFFENCES

[30] The 22 issues of Your Ward News were marked as Exhibit 2 at trial. The trial judge wrote:

After considering the entirety of Exhibit 2, a consistent and obvious theme that radiated from this publication was hatred. It was at times contradictory in that love was professed to Jews and some women. It was at times satirical in that humour and exaggeration were employed to make the point. But hatred of Jews and women was overwhelmingly the message.

[31] The trial judge went on to find that: (i) “both men intended to publish hate. No other intent can be inferred from a complete reading of this newspaper”; (ii) “there exists significant evidence of the promotion of that hatred which undeniably illustrates their intent to pass on to others the message of hate towards Jews and women”; and (iii) “both men were fully aware of the unrelenting promotion of hate in YWN and intended that hatred to be delivered to others.”

[32] The applicant appealed those findings, advancing his objections under several discrete grounds of appeal, contending that the trial judge: provided insufficient reasons; failed to read the publications as a whole and failed to consider the published words in their context; wrongly treated the 22 issues of Your Ward News as direct evidence from which he could infer intent; failed to consider alternate, non-criminal meanings for the published words; and misapprehended the evidence thereby rendering the verdict unreasonable. The Appeal Judge rejected the applicant’s objections.

[33] On these applications, the applicant repeats his challenge to the trial judge’s findings, organizing his complaints under two grounds of appeal contained in his Notice of Appeal and Notice of Application for Release Pending Appeal and Leave to Appeal: (i) the Appeal Judge improperly applied the test for promotion of hatred and erred in concluding that statements made by the applicant constituted promotion of hatred; and (ii) the Appeal Judge improperly applied the law relating to circumstantial evidence with respect to the issue of wilfulness.

[34] In comprehensive reasons, the Appeal Judge dealt with each submission. His reasons disclose that he:

i. correctly identified the applicable scope of appellate review: Appeal Reasons, at paras. 15-19; 23; 39-42; 49-50; 55; 57; 61; and 67;

ii. correctly identified the governing legal principles set out in R. v. Keegstra, [1990] 3 S.C.R. 697, and found that the trial judge had given himself the direction recommended in that case: Appeal Reasons, at paras. 31-33;

iii. accurately summarized the facts and principles in Villaroman, seeing no error in the trial judge’s finding that the contents of the 22 issues of Your Ward News constituted direct evidence of the statements made by the applicant from which the intention of the applicant could be inferred: Appeal Reasons, at paras. 34-37;

iv. on the latter point, properly referred to and applied the observation in Keegstra, at p. 778, that “[t]o determine if the promotion of hatred was intended, the trier will usually make an inference as to the necessary mens rea based upon the statements made”: Appeal Reasons, at para. 65;

v. Accurately read the trial judge’s reasons as stating that he had read the entirety of all 22 issues of Your Ward News, had assessed the statements made in context, and understood the distinction between hate speech and merely offensive or distasteful statements: Appeal Reasons, at paras. 33, 46, 58-61; and

vi. As part of the process of appellate review, reviewed the evidence of the issues of Your Ward News marked as Exhibit 2 at trial: Appeal Reasons, at paras. 56-61.

[35] That process of appellate review led the Appeal Judge to conclude, at paras. 58 and 61:

In his reasons, the trial judge found that “[w]hen all 22 issues are examined, one is left with unfocused and absurd opinions, contradictory messages, and scattershot ramblings. Except for its stated claims of being the world’s largest anti-Marxist publication, YWN exhibits no unifying concept.” This finding is reasonably supported by the evidence.

…

Based on my review of the published issues of YWN marked at trial as Exhibit 2, I am satisfied that there was ample evidence upon which the trial judge could reasonably make these findings and reach these conclusions. Statements described by the trial judge in paragraphs 11 and 12 of his reasons as communicating hatred, within the meaning of that term in Keegstra, against women and Jews are found in the issues of YWN received in evidence. The trial judge’s reasons show why he decided as he did, and they show a logical connection between why he decided as he did and the evidence that was the basis for his decision. The 22 issues of YWN received in evidence provide the basis for public accountability of the trial judge’s reasons. The trial judge’s reasons, read in the context of the evidence at trial and the submissions made by counsel, do not foreclose appellate review.

[36] The applicant has not identified any error of law that tainted the Appeal Judge’s analysis. As I understand his submissions, the applicant simply repeats his disagreements with how the trial judge applied the law to the specific facts of his case and complains that the Appeal Judge did not apply the law to the facts in a different way. This ground of appeal is fact-focused and does not engage a question of law alone.

VI. THIRD GROUND: APPLICATION OF S. 718.2(a)(i) TO OFFENCES UNDER S. 319(2)

[37] In his reasons for sentence, the trial judge identified, as an aggravating factor, that Criminal Code s. 718.2(a)(i) provides that “where offences are motivated by hate, the sentences ought to be increased.” That section deems to be an aggravating circumstance “evidence that the offence was motivated by bias, prejudice or hate based on race, national or ethnic origin, language, colour, religion, sex, age, mental or physical disability, sexual orientation, or gender identity or expression, or on any other similar factor.”

[38] In his factum on appeal, the applicant enumerated 10 errors committed by the trial judge in his sentence, including “misapplying Section 718.2(a)(i), as Parliament never meant it to redundify Section 319.” In his “Unfiltered Argument”, the applicant contended that since some speakers during the Parliamentary debate over the enactment of s. 718.2 gave examples of hate motivated crimes causing physical harm to people and the then Minister of Justice, Allan Rock, stated the proposed amendment had “nothing to do with policing or punishing the way people think or the views they hold”, it follows that s. 718.2(a)(i) applies only to violent crime against an individual. Since the applicant did not commit such a crime, he contends that the trial judge erred by relying on s. 718.2(a)(i) as part of his determination of sentence.

[39] In oral submissions, the applicant complained that the Appeal Judge failed to deal with his ground of appeal involving s. 718.2(a)(i). He contends that s. 718.2(a)(i) applies only to cases other than hate speech under Criminal Code s. 319.

[40] No doubt the proper interpretation of a provision of the Criminal Code involves a question of law. So, too, the proper interpretation of a provision of the Criminal Code is an issue of significance to the administration of criminal justice beyond the particular case. Yet, the applicant offers no arguable grounds for his position outlined above. On its face, s. 718.2(a)(i) applies to all offences in the Criminal Code; it identifies no exception. The applicant advances no plausible argument based on the principles of statutory interpretation that would create an exception where none exists.

[41] However, I have considered the applicant’s submission from a different angle. Perhaps the applicant is attempting to argue that by taking into account the statutory aggravating factors in s. 718.2(a)(i) the trial judge, in effect, impermissibly considered elements of the offence under s. 319(2) as aggravating factors. Characterizing an element of the offence as an aggravating factor is a reviewable error: R. v. Lacasse, 2015 SCC 64, [2015] 3 S.C.R. 1089, at para. 42; R. v. Adan, 2019 ONCA 709, at para. 106. Nevertheless, numerous cases have found no such error where a sentencing judge has taken into account statutory aggravating factors that are themselves elements of the offence: R. v. Tejeda-Rosario, 2010 ONCA 367, 262 O.A.C. 228, at paras. 12-13; R. v. B.S., 2019 ONCA 72, at para. 12; R. v. S.C.W., 2019 BCCA 405, at paras. 27-36; R. v. JAS., 2019 ABCA 376, at paras. 18-19. In any event, even where a sentencing judge errs, appellate intervention requires demonstrating that the error had an impact on the sentence. In the present case, the Appeal Judge considered whether the trial judge had erred by imposing a demonstrably unfit sentence. He concluded, at para. 136, that the applicant had not shown that the trial judge imposed a demonstrably unfit sentence. The applicant has not identified any arguable error of law in the Appeal Judge’s review of this aspect of the sentence.

[42] Consequently, this ground of appeal does not satisfy the principles in R.R.

VII. FOURTH GROUND: IMPOSITION OF CONSECUTIVE SENTENCES

[43] The trial judge sentenced the applicant to the maximum sentence of six months on each of the two counts, to be served consecutively. In determining that the sentences should be consecutive, the trial judge applied the decision of this court in R. v. Gummer (1983), 1 O.A.C. 141, [1983] O.J. No. 181 (C.A).

[44] Gummer involved convictions for dangerous driving and failing to stop. In setting aside the imposition of concurrent sentences and making them consecutive, this court stated at para. 13:

We do not consider the rule that sentences for offences arising out of the same transaction or incident should normally be concurrent necessarily applies where the offences constitute invasions of different legally-protected interests, although the principle of totality must be kept in mind. The offences of dangerous driving and “failing to remain” protect different social interests. The offence of dangerous driving is to protect the public from driving of the proscribed kind. The offence of failing to remain under s. 233(2) of the Code imposes a duty on the person having the care of a motor vehicle which has been involved in an accident, whether or not fault is attributable to him in respect of the accident, to remain and discharge the duties imposed upon him in such circumstances.

[45] The trial judge stated, at para. 12:

In this case, identifiable groups, those being women and Jews, have separate, legally-protected interests. The defendant could promote hatred against one and not the other, or vice versa. He promoted hatred against both. In addition, the hate was promoted against both groups not from one incident, but many, and consistently over a period of three years.

[46] On his appeal from sentence, the applicant submitted that the trial judge committed an error in principle by deciding that the sentence for each count should be served consecutively rather than concurrently. The Appeal Judge did not accept that submission. The Appeal Judge properly recited the deference owed to a sentencing decision absent an error in principle or demonstrably unfit sentence. In the case before him, the Appeal Judge concluded that the trial judge did not err in principle by ordering that the sentence on each count be served consecutively, stating at paras. 129-130:

Counsel for Mr. St. Germaine submits that the only relevant interest for a sentencing judge to consider is society’s interest, and that the trial judge erred by identifying two separate interests. I disagree with this submission. Society has an interest in discouraging hate crimes against different groups and, just as in Gummer, the trial judge concluded in respect of the charges against the appellants, that there were two separate societal interests, discouraging hatred against women and discouraging hatred against Jews.

The Crown proceeded with a two-count information against each appellant and it acted within its discretion to do so. The trial judge had reviewed the collection of the 22 issues of YWN that were introduced into evidence, and he was well situated to decide whether the communications against women and against Jews in those issues should properly be treated as part of the same conduct against two groups who do not not enjoy separate protected interests, such that concurrent sentences would be proper. The trial judge, having reviewed the 22 issues, concluded that the communications promoting hatred were directed against separate identifiable groups, women and Jews, and each has a separate legally protected interest.

[47] On this application, the applicant submits that the Appeal Judge erred in law in allowing the order for consecutive sentences to stand.

[48] I am not persuaded that this ground of appeal amounts to a “question of law alone”. The Appeal Judge properly identified the principles governing his appellate review of the trial judge’s sentence. The applicant does not identify any conflict within the jurisprudence relevant to the circumstances of his sentence. Finally, as pointed out in Clayton C. Ruby, Sentencing, 10th ed. (Toronto: LexisNexis, 2020), at §14.18, “it becomes a fact-specific inquiry of whether the nexus between offences is sufficiently or insufficiently close to merit either consecutive or concurrent sentences.” [Emphasis added.]

VIII. DISPOSITION

[49] For the reasons set out above, I am not satisfied that the applicant’s proposed appeal meets the requirements of Criminal Code s. 839(1), as interpreted by R.R. Accordingly, the application for leave to appeal is dismissed. It follows that the application for bail pending appeal is also dismissed.

“David Brown J.A.”

[1] Section 839(1) of the Criminal Code states, in part: “Subject to subsection (1.1), an appeal to the court of appeal as defined in section 673 may, with leave of that court or a judge thereof, be taken on any ground that involves a question of law alone …” [Emphasis added.]

[2] The decision of this court in Woods (Re), 2021 ONCA 190, 154 O.R. (3d) 481, to which the applicant directed my attention, has no application to the present case. Woods involved proceedings under Part XX.1 of the Criminal Code. This court held, at para. 33, that Part XX.1 of the Criminal Code did not provide the Ontario Review Board with the authority to conduct its hearing by videoconference without the consent of the NCR accused. Part XX.1 has no application to the present case, which concerns the powers of judges on summary conviction appeals.